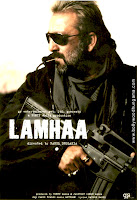

Lamhaa is only the latest film to remind us that the Kashmir problem demands the attention of the film-going public

India has no shortage of conflict zones. Almost every state in the North-East, especially Manipur, continues to challenge Delhi’s authority. Although Punjab has put the horrific 1980s behind it, members of the Babbar Khalsa militant outfit continue to emerge out of the state’s mustard fields at periodic intervals (perhaps their peace has been disturbed by the number of Bollywood crews that have descended on the place). The Maoists are here, there and everywhere. Yet Bollywood remains most worried about the fate of Jammu and Kashmir. Lamhaa is only the latest film to remind us that the Kashmir problem demands the attention of the film-going public.

The renewed surge of police firing and stone pelting in Kashmir has given Lamhaa the kind of publicity that cannot be bought. However, film-makers don’t seem as exercised about Manipur, home to regular blockades, extra-judicial killings, and one of the most searing protests ever captured by cameras in the history of independent India. On 11 July 2004, 32-year-old Thangjam Manorama was gangraped, mutilated and killed, and the evidence pointed to an Assam Rifles unit. On 15 July, 12 women marched under the banner “Mothers of Manipur” and stood naked for hours outside the headquarters of the Assam Rifles in Kangla Fort screaming “Indian Army come rape us”. Few national newspapers and magazines had the guts to print the photographs. Not even the most imaginative screenplay writer could have come up with such fierce and tragic imagery.

The North-East has always been a foreign land whose inhabitants are racially and culturally removed from the rest of India. A favourite past-time during summer holidays used to be the “Guess the capital of the state” game. Even class-topping cousins would invariably confuse Aizawl for Kohima and Shillong for Gangtok. An entire chunk of the Indian map fell off from view so long ago that it requires serious political commitment to rediscover it. Besides, the problems of states such as Nagaland and Manipur are so complex and involve so many parties and tribes that only historians and journalists can be relied upon to make sense of the situation. Kashmir, despite harbouring several Hurriyat Party members with similar appearances and long-winded names, is far easier to comprehend.

A few film-makers have dared to shift the gaze away from Kashmir. Kanika Verma’s Dansh (2005), based on Chilean playwright Ariel Dorfman’s Death and the Maiden, explored militancy and ceasefire efforts in Mizoram. However, Verma inexplicably got Kay Kay Menon, Aditya Srivastava and Sonali Kulkarni to play Mizos. Mani Ratnam’s Dil Se, about the Assam insurgency, at least had Manisha Koirala play a suicide bomber. Assam has produced some fine actors on the stage and in the movies (Seema Biswas, Adil Hussain), but North-Eastern faces are still too exotic to be treated on a par with the rest of India.

Kashmir will always be deemed as the prickliest thorn in the side of the Indian state, especially because India has gone to war with Pakistan over Kashmir. Besides, nothing stirs the soul more than a paradise lost. Kashmir provides ready contrasts of beauty and brutality. A soldier’s protruding gun in the foreground, a gaggle of rosy-cheeked children in the background. Shimmering mountains sheltering Kalashnikov-wielding insurgents. The state’s sad journey from tourism to terrorism will never stop inspiring headlines, poems, documentaries and movies. If Kashmir ki Kali reminds us of what we once had unfettered access to, Roja warns us of what we have lost. If there is a shooting paradise on earth, it is here, it is here, it is here.

Lamhaa released in theatres on Friday.

**Nandini Ramnath is a film critic with Time Out Mumbai

No comments:

Post a Comment